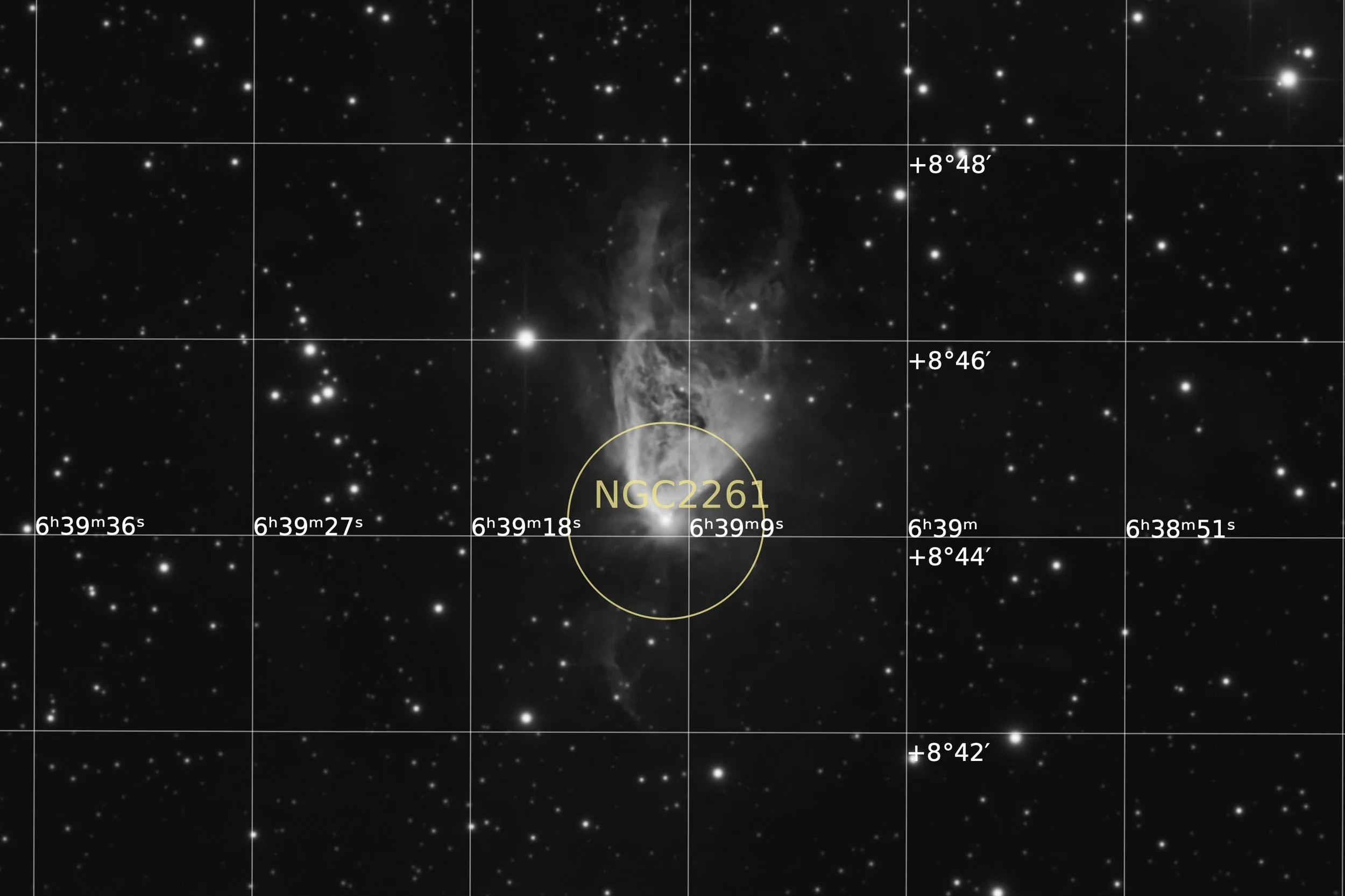

Caldwell 46

NGC 2261, Hubble's Variable Nebula

13’ x 9’ | 0.3”/px | 2728 × 1818 px | full resolution

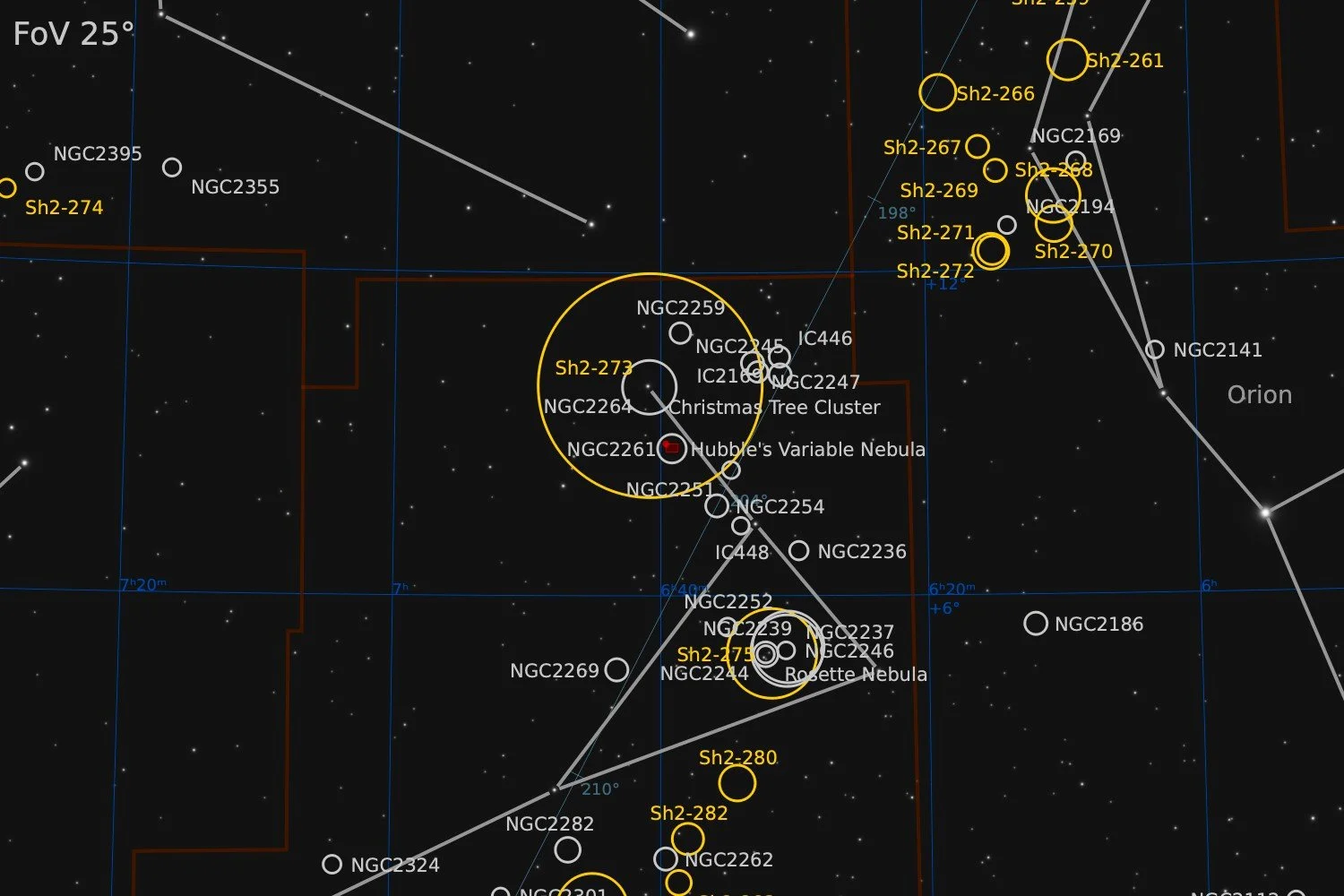

Monoceros

RA 6h 39m 10s Dec +8° 44’ 54” | 0°

Caldwell 46, also known as NGC 2261 or Hubble's Variable Nebula, is a variable nebula located in the constellation Monoceros. The nebula is illuminated by the star R Monocerotis (R Mon), which is not directly visible itself. The first recorded observation of the nebula was by William Herschel on 26 December 1783, being described as considerably bright and 'fan-shaped'. It had long been designated as H IV 2, after being the second entry of Herschel's class 4 category for nebulae and star clusters, in his catalogues of nebulae. Caldwell 46 was imaged as Palomar Observatory's Hale Telescope's first light by Edwin Hubble on January 26, 1949, some 20 years after the Palomar Observatory project began in 1928. Hubble had studied the nebula previously at Yerkes and Mt. Wilson. Hubble had taken photographic plates with the Yerkes 24-inch (60.96 cm) reflecting telescope in 1916. Plates were taken using the same telescope in 1908 by F.C. Jordan, allowing Hubble to use a blink comparator to search for any changes over time in the nebula. A timelapse of NGC 2261 was taken over a period of 6 months by over 20 amateur astronomers at the Big Amateur Telescope from October 2021 – April 2022. In August 2022, the project was resumed as NGC 2261 came out from behind the Sun. Light 'ripples' can be seen propagating, at light speed, from the central star as it varies in intensity and illuminates the surrounding nebula. The star R Monocerotis has lit up a nearby cloud of gas and dust, but the shape and brightness slowly changes visibly even in small telescopes over weeks and months, and the nebula looks like a small comet. One explanation proposed for the variability is that dense clouds of dust near R Mon periodically block the illumination from the star. This casts a temporary shadow on the nearby clouds.

Source: Wikipedia

Data Acquisition

Data was collected during 12 nights from September 2025 until January 2026, using a 14” reflector telescope with full-frame camera at the remote observatory in Spain. Data was gathered using standard LRGB filters. A total of approximately 16 hours of data was finally combined to create the final image.

Location Remote hosting facility IC Astronomy in Oria, Spain (37°N 2°W)

Sessions

Frames

Equipment

Telescope

Mount

Camera

Filters

Guiding

Accessoires

Software

Planewave CDK14 (2563mm @ f/7.2), Optec Gemini Rotating focuser

10Micron GM2000HPS, custom pier

Moravian C3-61000 Pro (full frame), cooled to -10 ºC

Chroma 2” LRGB unmounted, Moravian filterwheel L, 7-position

Unguided

Compulab Tensor I-22, Dragonfly, Pegasus Ultimate Powerbox v2

Voyager Advanced, Viking, Mountwizzard4, Astroplanner, PixInsight 1.9.3

Processing

All processing was done in Pixsinsight unless stated otherwise. Default features were enhanced using scripts and tools from RC-Astro, SetiAstro, GraXpert, CosmicPhotons and others. Images were calibrated using 50 Darks, 50 Flats, and 50 Flat-Darks, registered and integrated using WeightedBatchPreProcessing (WBPP). The processing workflow diagram below outlines the steps taken to create the final image.

The latest version of the WeightedBatchPreProcessing (WBPP) script in PixInsight, version 2.9.1, includes a so-called frame selection step. In essence this is the SubFrameSelector tool, but much easier to use. In most cases you will want to use this step in the interactive mode. It will present you with an overview with image statistics of all frames, and several graphs showing how each subframe scores on image parameters such as FWHM, eccentricity, # stars, etc. I applied this method for the first time during processing of Caldwell 46. It is difficult to pinpoint exact values for which frames should be included and which not, but you do get a very good feel for general image quality and outliers. The data for this image was collected over many days, spanning a period of 4 months, and often the conditions were not great. So my dataset definitely showed quite some variation. In total I set the parameters such that about 3.5h of exposure time was not included in the finale stacks. The question then remains if the final stacks were of better quality then when all frames would have been included and dealing with quality differences was left solely to the weighting mechanism. For one stack, the blue channel, I processed with and without the discarded frames. Applying frame selection during stacking resulted in about a 10% improvement in both FWHM and eccentricity values. So overall it is well worth to at least include the frame selection step in the preprocessing. And in setting the pass parameters you can be more or less restrictive in the amount of frames that will be discarded. Overall this is a very welcome extra functionality in WBPP, that will be part of my processing flow from now on.

The bright star HD 261389 to the left of the nebula showed a few minor color artefacts. During a recent presentation for The Astro Imaging Channel (TAIC), Mike Banfield presented the script PixelMathUI (PMUI), One of the applications he showed was PixelMath code to make star repairs. With that code, I created a scriptlet in PMUI and corrected the minor color artefacts. This worked very easy and gave pleasing results.

The rest of the processing used a fairly standard approach, outlined below.

Processing workflow (click to enlarge)

This image has been published on Astrobin.